Why Atheists Need No (Religious) Faith

What we need Is rigorous, consistent definitions

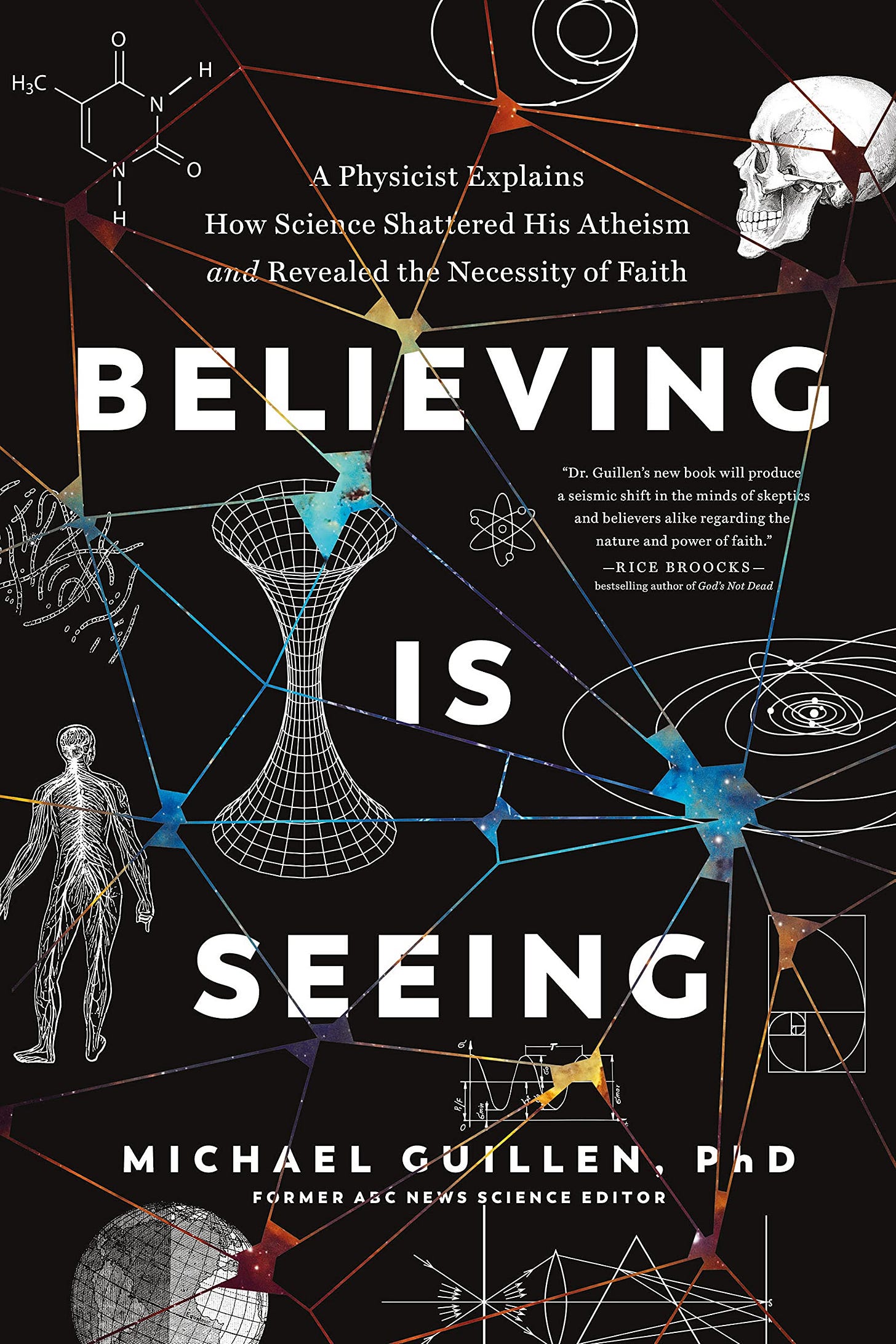

A while back, Google (correctly) suggested I might be interested in a Wall Street Journal guest opinion article titled “Why Atheists Need Faith.” Being something of a devout atheist, I felt compelled to read it. Then I felt inspired to write this (longer) rebuttal. I’m going to summarize the article’s position and quote some key lines, but you should go read it yourself of course. The article isn’t long and the WSJ paywall should let you through if you google it.1 ( Just think of all the time we’re saving by not having to read the actual book.)

To summarize the article, mostly charitably:

Atheism is supposedly based on science and reason, but even science requires unprovable axioms as a basis, which means it requires faith. Additionally, the limits of science make religion necessary to deal with the mysteries of the universe, which atheism cannot account for. Therefore, religious faith (specifically Christianity) is justified. Checkmate, atheists. You’re just like us, but your worldview is inferior because it is more limited.

The main trick here is to apply words like “faith,” “proved,” and “axiom” to different claims, as if they are the same labels at all times and in all things and in all places, and therefore equally justifiable in very different use cases. Kind and degree matter, however, as does specific context. If you didn’t notice when reading the article, the author never actually defines what he means by “faith.” Seems like a significant omission, particularly because the word “faith” is a classic hang up in religious arguments due to the varying connotations in different contexts (as we will explore). One of the weak points of language is that a given word can mean different things in different contexts. Many subpar arguments are made by refusing to recognize that the mere label is not itself the underlying meaning, let alone a suitable representation of reality to another mind.

The piece begins:

Atheism’s central conceit is that it is a worldview grounded in logic and scientific evidence. That it has nothing to do with faith, which it associates with weakness.

Leaving aside whether atheism—the nonbelief in deities in its most basic sense—is itself a worldview vs. a characteristic of actually robust worldviews (e.g., Humanism), it is true that in a modern, Western(ized) context those who self-identify as atheists do generally claim to base their views on a scientific epistemology. These kinds of rascally science-based atheists would indeed say their lack of belief in deity is not based on any faith, as they understand the term in a religious context. Rather than simply “weakness,” I think we atheists associate religious faith with something like: “Insufficient or inappropriate evidence for a claim—usually religious or spiritual in nature—resulting in an unjustified belief.” So sure, faith is used to believe claims associated with weak evidence. So far, so good then?

Well, not really, because we might agree with the description using my definition of “faith,” but somehow I doubt the author would accept it. My best guess is that his definition of faith is something like: “Belief in a claim that does not have tangible evidence or may not be provable, but is nonetheless justified, whether in a secular or religious context.” That’s my best, charitable guess, but I’m not sure he is consistent with his use.

He goes on:

All worldviews are built on core beliefs that cannot be proved. Axioms from which everything else about a person’s perception of reality is derived. They must be accepted on faith.

Even reason itself—the vaunted foundation of atheism—depends on faith. Every logical argument begins with premises that are assumed to be true. Euclid’s geometry, the epitome of logical reasoning, is based on no fewer than 33 axiomatic, unprovable articles of faith.

Great, so let’s examine “faith,” “axiom,” and “provable.”

Faith

Consider the following sentences:

I have faith in you.

He was always faithful to his wife.

He faithfully discharged his duties.

Now faith is the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen.

I have faith the sun will rise tomorrow.

She was not arguing in good faith.

The word faith then can at various times mean “belief,” “hope,” “trust,” “fidelity,” or “sincerity,” and it can be applied in routine ways that do not remotely conflict with secular living or scientific reasoning. Sure, any belief about the future is necessarily based upon some degree of imperfect knowledge. But it’s wildly different to have faith in the sun rising than it is to have faith in winning the lottery, as a matter of clear probability. The former is near absolute as a matter of physics and established precedence; the latter astronomical for any one ticket (though a ticket will win2). Similarly, knowledge about the distant past often relies on imperfect evidence, but there’s an incredible gap between believing (a) Rome was the capital of the Roman Empire and (b) that the Roman god Jupiter controlled (controls?) the weather and tosses thunder bolts about3. Having justifiable levels of confidence in a belief is proportional to how much suitable evidence exists relative to the level of claim under consideration (and relative to competing explanations). “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” as the saying goes. Confidence should correspond to justifiability. Reasonable faith covers the gap yet unfilled by evidence.

In the context of religious faith, however, there is typically a sense of confidently held knowledge despite the lack of evidence normally required for significant claims. Or in the face of overwhelming counterevidence. Religious faith is necessary because it is held regarding religious beliefs for which incontrovertible hard evidence is unavailable—like the existence of any particular god. One cannot “trust in God” without first believing in His (or Her) existence, after all. So faith as belief is quite different in the context of a routine claim with suitable evidence than it is when referring to a significant claim without appropriate evidence. The former is perfectly justified by regular epistemic practices; the latter conflicts with reason and scientific standards of evidence. In a religious context then, “faith” becomes shorthand for the overall religious epistemology. “Faith in [deity]” is a different use case of “faith” than “faith in the sun rising,” based on the nature of the claim and available evidence.

Check out this LDS children’s song I happened across when I was trying to see if anyone talks about having faith in the sun rising4:

Faith is knowing the sun will rise, lighting each new day.

Faith is knowing the Lord will hear my prayers each time I pray.

Faith is like a little seed:

If planted, it will grow.

Faith is a swelling within my heart.

When I do right, I know.

Faith is knowing I lived with God before my mortal birth.

Faith is knowing I can return when my life ends on earth.

Faith is trust in God above;

In Christ, who showed the way.

Faith is strengthened; I feel it grow

Whenever I obey.

I’m not going to unpack everything that’s going on here, but you can clearly see the transition from “belief in a totally mundane thing with tons of uncontroversial, observable evidence” to “belief in this religious claim with controversial, unobservable evidence.” That’s the trick, along with some not-so-subtle emotional conditioning for small children.

Axioms

It is correct, but trivial, to say that axioms are required as a basis for, like, everything (something has to stop the “turtles all the way down”). However, the author does not seem to recognize the difference between a justifiable premise and an unjustifiable one. Not all premises are created equal and by their fruits ye shall know them.

The only axiom from which I build everything else is that my consciousness is self-evident and irreducible (to me; get your own). Perception is indeed reality in that sense, even if I can use my perception to recognize there seems to be an external reality independent of my limited perceptual faculties. Beyond that bit of absolute confidence in my existence as a conscious being on a self-evident axiom that I cannot definitively prove to anyone else, everything else is a bit more conditional and probabilistic. You gotta take these things on a case-by-case basis.

So, sure, the axioms upon which Euclidean geometry is based are unprovable by strict standards of formal logic, but they are very far from “unprovable articles of faith.” Go read them. One is the definition of a point. Another is the definition of a line being what connects two points. It goes on to define a circle. Hell, we’ve known for nearly a century now from Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, Tarski’s undefinability theorem, and the Munchhausen trilemma that even math and logical systems cannot be grounded in provable axioms within a self-contained system. This is not a strong blow against science as an epistemology, since any logical system is going to suffer from these issues. (“Well let’s use an illogical one then” is not a convincing alternative.)

Even better is that we can empirically test the fruits of Euclidian geometry against reality and demonstrate it is a reliable and accurate tool. Been on a bridge lately? Like Newtonian physics, it remains in everyday use for the common world, though we have developed an understanding of its limits from special relativity and quantum mechanics. Humans were profitably using Euclidian geometry long before all of the necessary axioms were even identified because it faithfully (pun intended) correlates with reality to a useful degree. What the actual axioms are for any given belief system in terms of justifiability matter greatly. So do the resulting predictions and their correlation to reality.

Provable

Definitive, absolute proof is a tall standard in a complex world. All axioms are not equally justifiable and proof as the author invokes it is a red herring for self-evident axioms. The author doesn’t mention how many axioms are needed for his faith, but he cannot say his faith sets a rigorous standard for proof that science cannot match. I would question whether the author is using the same definition of the word and a fair standard of evidence for given claims across contexts. It seems unlikely, since he wants to focus on the technicality of unprovable axioms as a necessary starting point, which many readers won’t understand are very different from say the results of Euclidean geometry proving its accuracy every time some school kid calculates the Pythagorean theorem.

Since religions tend to lack obvious proofs to the incredulous, he has to try to obfuscate and drag science down to the level of his apparently baseless faith to make them seem equally (un)justifiable. Science—whatever its limitations and mistakes—obviously works5 as a powerful epistemology. Religious faith does not. If faithful approaches at knowledge acquisition worked, science would have never needed to exist independent of religion and we wouldn’t be bothering with articles like this.

Worldviews, Their Size, Their Ruler(s), and Their Darkness

Second, size. Every worldview—that is, every person’s bubble of reality—has a certain diameter. That of atheism is relatively small, because it encompasses only physical reality. It has no room for other realities. Even humanity’s unique spirituality and creativity—all our emotions, including love—are reduced to mere chemistry.

Are the diameters of “bubbles of reality” not dictated by, like, actual reality? His accusation here is trivially true in that the kind of scientific atheists he’s aiming at tend to be materialists, believing matter and energy are all there is. (If you have something else to offer, we look forward to you receiving your Nobel Prize.) What is the mind if not the result of a brain made up of chemicals and energy? What emotions cannot be explained by what happens in the mind? How does he know? What are these “other realities” totally beyond the reach of science? Figments of someone’s imagination? How does he know? “Mere chemistry” is all we have! And it has a lot of explanatory power, unlike mere Christianity. If it isn’t all we have, how would we tell? Say we have spirits that are somehow neither material nor energy, how are they interacting with physical reality such that it’s undetectable? To be more direct, how far off his rocker is this guy to have a modern understanding of physics and yet somehow believe human spirituality and creativity is totally beyond the means of science to explain in terms of origins in the mind?

Third, deity. Without exception, every worldview is ruled over by a god or gods. It’s the who or what that occupies its center stage. Everything in a person’s life revolves around this.

This point illustrates the fact that, almost without exception, theists cannot accurately conceive of a lack of theism. They can’t even pretend to model it in my experience (which is the most charitable explanation I think for all the strawman versions of atheism out there). This statement is pure projection and accuses atheists of being in denial of what's in their own heads regarding deities. Think of the conceit that takes! By comparison, we atheists just want to point out that the imaginations in theists’ heads don’t seem to correspond to external reality insofar as we can measure it—a far humbler accusation really. For those of us who grew up believers, we can assure you our lives and thought patterns were quite different when we believed in god(s). I’ve had the distinct privilege to be an atheist-not-in-a-foxhole taking indirect fire on a few occasions. Never did I think to pray.

[M]y [previously atheistic] worldview rested on the core axiom that seeing is believing. When I learned that 95% of the cosmos is invisible, consisting of “dark matter” and “dark energy,” names for things we don’t understand, that core assumption became untenable.

I fail to understand why someone would so rigidly believe “seeing is believing” is a good solitary axiom for an atheism based on scientific reasoning. Maybe it was because of the sleep deprivation (read the article!). Sight is but one sense if we’re being literal, and science has always been a small, dim flashlight shining into the immense, dark universe if we’re being figurative. But the light is on. The author is only aware the universe is 95% invisible because science made that estimation, not because his faith tradition figured it out. Encountering a phenomenon one doesn’t understand and then concluding “faith in God is the answer” is a classic god of the gaps argument and, again, fails because it is responding to a mysterious questions by believing in an even more mysterious answer. Does this guy also not understand how magnets work6? Using an inexplicable deity to explain the inexplicable is just kicking the can down the road, not answering any fundamental questions about reality. I guess I can see how, on a superficial level, it’s emotionally comforting to believe some higher power has it all figured out. We atheists are simply forced to humbly accept the current limits of our understanding.

Because what we hold to be true dictates how we understand everything—ourselves, others and our mostly invisible universe, including its origin. Faith precedes knowledge, not the other way around.

Atheism demands a small cosmos, so that is all secularist-materialists see. They bend over backward to interpret every pixel of evidence solely in terms of space, time, matter and energy. For them, that’s all there is. It’s a religious conviction they cannot prove but take on faith.

Here, he is clearly establishing faith to be an epistemology. Only problem is saying that “faith precedes knowledge” is begging the question of alternative epistemologies. Science as an algorithm of iterative trial and error, hypothesizing and testing, and a body of knowledge always open to new evidence and subject to revision, requires no faith of the religious sort to deal with uncertainty and humanity’s limited faculties of comprehension. We’ve had a few centuries of using science consistently and gotten pretty good results overall. That’s why I’m writing this on a machine made of dirt we zapped with lightning and tricked into thinking7 and you’re reading it after it was transported over a series of tubes.

Let me make the bold claim that atheism, using a scientific approach, just does not demand any particular size of cosmos. We want to believe the cosmos is exactly as big as it is. This is because science does demand rigorous adherence to reason and evidence. Otherwise, it’s not an effective tool. There is no bending or pretending required to accept reality as it is. There is no conviction that cannot be overturned by subsequent evidence. What does require bending over backward is pretending that religious faith is an accurate lens with which to view the cosmos, that it can in any way compete on equal grounds with scientific reasoning, and that religions as traditionally conceived have anything of value to offer on matters of epistemology8.

Atheists commonly believe that science will ultimately demystify everything. But science’s worldview is becoming more mystical, not less. Witness supernatural-like concepts such as virtual particles, imaginary time and quantum entanglement. Even atheist Sam Harris admits: “I don’t know if our universe is, as JBS Haldane said, ‘not only stranger than we suppose, but stranger than we can suppose.’ But I am sure that it is stranger than we, as ‘atheists,’ tend to represent while advocating atheism.”

Do we though? Everything? I think we tend to believe science as an epistemology is our best chance at understanding anything (religions remain welcome to give it their best shot), not an all-powerful tool that will conquer every possible mystery. Any reasonable person has to accept the limitations of knowledge and calibrate their confidence according to the availability of appropriate evidence. Our minds are imperfect and science, properly executed, is a way to account for those limitations by systematically testing claims against reality.

The universe is a weird place and the fact that “even Sam Harris” can acknowledge that seems like evidence atheists aren’t going to suddenly find reason to believe in deities due to the potential incomprehensibility of the universe. Responding to scientific mystery by invoking unscientific mystery remains a nonsensical approach. The strangeness of the universe as revealed by science is in stark contract to mysterious gods resisting detection by those scientific means.

Faith is the foundation of the entire human experience—the basis of both science and religion. Our faith in physical reality drives us to seek treatments for deadly diseases like Covid-19, to explore the depths of the sea, to invent the perfect source of energy. Our faith in spiritual reality drives us to create breathtaking works of art, music, and architecture; to see life as a divine creation, not an accident of nature; to be curious about things that are not of this world.

If he wants to define faith here as “a lack of perfect understanding” then I can agree. No one’s perfect. Ignorance is the unavoidable starting point. It is nice to see the explicit dualism of physical vs. spiritual reality. But life’s creation is part of the spiritual reality? What exactly is “not of this world”? How does he know? Doesn’t architecture make heavy use of Euclidean geometry? Science is constrained by actual reality, not the wideness of our imaginations. This is a feature, not a bug!

Leaving aside the incoherent compartmentalization of physical and spiritual worlds, he does seem to be inadvertently admitting that a physically focused scientific epistemology is intrinsically incompatible with a spiritually focused religious, faith-based epistemology looking at spiritual reality, such as it is. The problem there is that the physical and spiritual realities unavoidably overlap, and science seems like the clear winner across the board. Where the spiritual reality doesn’t overlap, uh, what exactly even are we talking about?

In Conclusion

"The word “faith” in (secular) common parlance and “faith as a religious epistemological term” are distinct concepts.

No, atheists don’t need faith in any religious sense of the word as the basis for a scientific epistemology.

The limitations of science do not excuse the limitations of religious faith because there is a fundamental asymmetry between the types of claims, the available evidence, and the demonstrable results.

Recognizing the limits of science is not an argument for the existence of a deity; it is an argument for skepticism about extraordinary claims trying to hide in the gaps.

URL: https://www.wsj.com/articles/atheists-need-faith-christianity-science-reason-physics-math-astronomy-11632426886

Conflating the astronomical chance of a specific outcome with the fact something must occur is also a common error in reasoning. It’s not a miracle someone wins the lottery.

Ah, well, nevertheless.

I have no recollection of this song. My wife, however, started singing it when I asked her.

I am paraphrasing the witty remarks of others. Perhaps the mystery of lightning shows Jupiter is powering all of our CPUs.

It’s beyond of the scope of this essay, but religions—at least parts—are clearly not valueless in every respect. That’s one reason they survive.

I think you did a good job expressing you arguments clearly and fairly representing the position you argue against.

However, I think that the motivation of people who argue that atheists need religion was not addressed and it would be important to do so.

If you don't mind me plagiarizing my own comment from a different post on Substack("Why Being Religious Doesn't Make You a Bad Scientist" by J. Venere), here it goes:

"You don't have to justify your beliefs."

I am of the opinion that anything that can be destroyed by truth should be destroyed by truth.

"It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so." - Mark Twain

There's Atheism 1.0 and then there's Atheism 2.0.

Atheism 1.0 is how one could describe a zealot who has simply traded one God for another. It's hard to give up the comfort of something that stirs one's rage towards others while quieting the rage towards oneself - that's a powerful God that's hard to renounce.

Atheism 2.0, coined by philosopher Alain de Botton, recognizes that religious culture provides for psychological needs that don't simply go away because one can eviscerate Scripture with facts and logic. Rituals are an important part of religious culture because the are meant to remind of us of important things were are likely to ignore otherwise. For example, the Jewish ritual of Birkat Ha'llanot(Blessing for A Blossoming Fruit tree) makes it so that every year, in the month of Nisan(March-April on the Gregorian calendar), you go to a blossoming tree and recite a blessing. From a purely secular perspective, it still has value due to it's insistence that you schedule time to appreciate the beauty of the flowers and the fruits that they promise. The scheduling part is important, because if you leave it to chance, you're likely to forget about. I mean, when's the last time you thanked a blossoming tree? I can't say that I remember.

As for the place of God in science, Pierre- Simion Laplace observed(correctly, I think) that "I have no need for such a hypothesis"), which is apparent via Occam: why tack burdensome, vague, unproven details onto an explanation?

I would say there is similarity between spirituality and the scientific worldview. Both require humility and a willingness to accept that nature operates how it pleases, even if that doesn't agree with how we think it should work. The difference between spirituality and the scientific world view seems to be that science respects the unknown and does not caricature it into a shape that is merely a product of our imagination, a scribble on a map with that has no corresponds solid ground equivalent.